On Friday we analyzed an image of Graham Company dancers in a strike pose, noting how it illustrated the opposing forces at work in both the form and content of Steps in the Street. Here, the conflict of the mass is of the individual’s experience being experienced communally – and it seems like this friction is inherent in the act of reconstructing itself.

Throughout the first rehearsal Jennifer Conley has emphasized an “intermingling” that should occur – between the steps and the students. Because this piece is alive with history there must be a negotiation between the “then” and the “now” in the dynamic process of its recreation.

The tragedy of Miss Graham’s art is that like all dancing it is bound up with time and space, that is, ephemeral unless it can in some way be fixed. (Re-Radicalizing Graham)

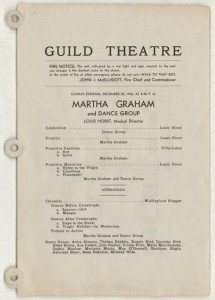

This statement, made by composer Wallingford Riegger, indicates how important reconstructions are to dance history. This was not recognized by Martha Graham herself, however, for nearly three quarters of her career – she rarely kept her early pieces, notoriously destroying films and photos of them. It was not until she stopped performing in 1969 (at the age of 75!) that this changed, and her first sanctioned revivals of early works did not make it to the public until the late 1980’s.

It is seemingly by a stroke of luck that Steps survived! While other sections from Chronicle have been revived some are only fragments of what they had been – re-staged largely from dancers’ memories – and the larger work in its entirety is considered irretrievable.

In the mid-1980’s partially destroyed and silent footage of the original 1936 production of Chronicle, filmed by the ethnographer Julien Bryan, was found in the depths of a vault. It was by weaving together sections from Bryan’s footage with some recreated choreography that Yuriko (associate artistic director of the Company at this time), supervised by Martha Graham, revived Steps in the Street nearly 50 years after it had been lost.

Though the musical score of 1936 could not be found a different work by its original composer – Riegger’s New Dance – accompanies Yuriko’s reconstruction. This revival of Steps in the Street premiered in October of 1989 during the Martha Graham Dance Company’s Fall Season at New York’s City Center.