I’ve been reading people remark upon how her dances from the ‘30s, her earlier dances, don’t have the sleekness of her later dances, which were informed by more balletic shapes and gestures. These early works were really about the power of the mass, the unified group of women—and her company was all women at that time—so, when you reconstruct at other schools is it always an all- female cast? I always have a female cast for these early works. I’m not opposed to having men in the piece—I mean at the Graham Company the men always wanted to do Chronicle, which is the bigger piece that this is a section of— they wanted to do a male version of it—but, not yet…

…Well there’s a certain authenticity, I guess—the costuming would change, the male body has a different presence—Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman were working alongside Martha, in another part of New York but at the same time, and they were doing the male-female-equal thing—the no struggle for dominance of one over the other but trying to exist harmoniously, cooperatively, and creating this sort of Utopian society of men and women, and Doris choreographed for the women and Charles choreographed for the men—so there’s an egalitarian sort of feeling that was in the air—it affected them and it affected Martha too.

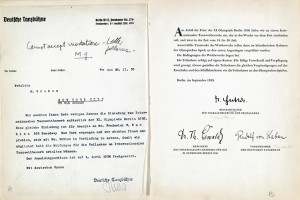

A lot of Martha’s dancers actually were involved in something called the New Dance Group, which was a radical dance collective that really thought that dance could incite social change, their slogan was, “Dance is a weapon to incite social justice,” and they were really into dancing on the picket lines, and helping with the unionization movement that hadn’t quite formed yet—Martha wasn’t that closely tied with it, but she knows the headlines, she knows what’s going on, she knows who her dancers are and where they’re coming from—from Russia, from Germany, from all these different places, a high Jewish percentage of women in her company, who grew up in the tenement housing on the Lower East Side, working class families—so she’s aware, consciously, of what’s going on.

So when these fears are swelling, among the people on the east coast, with regards to what’s happening abroad, it’s real for this generation of artists—they didn’t see themselves as separate from this, they saw themselves as part of it—and so how is my art going to reflect that? And there’s such humanity in the work of the 1930s.

They call them “The Greatest Generation”—it’s a different spirit, it’s a different sense of mankind and our relationship to one another, than we have today. I don’t think there was any apathy—things did not come as easily, in terms of information, or even food for that matter, or jobs (though we are having a downturn in our economy right now in terms of jobs – )…but, yeah, it was such a different time and it wore on the people differently. So the way they moved was different.

Yeah. I was just thinking, the way they moved in terms of the way their bodies were informed by their surroundings—and by their own thoughts and personal and political motivations—but also thinking about the food that they’re eating and the clothing that they’re wearing, whatever is available— Double knit wool!

[Laugh] Right. I guess they refer to this as her “long woolens period”— That’s right.

…thinking about your material goods and how that is affecting your performance—and your body and the way that you’re living—yeah, dancing in wool… It’s before lycra, it’s before nylon—and it’s also a time too for women—America is still waking up from the Victorian protocols, expectations on women, and there’s this quickening of city life, because these artists were all living in New York City. The skyscrapers were going up and you’re seeing these bold geometric lines, like the Chrysler Building or the Empire State Building, which went up around the same time these dances were happening.

There’s a similar “economy of means” they like to say when they are analyzing these buildings, in that there’s some simplicity there. And we’re not looking at the ornamental nature of, say, Grand Central Station, which is one of my favorite buildings in New York City, with the Baroque curlicues… We’ve completely gone into something very stark and very minimal.

The stark and minimal strike pose seen repeatedly throughout “Steps”

Yes—the strong defined lines of this dance, the geometry of it, is something—just now watching it appear on stage for the first time—that I was able to appreciate in a whole new way. It’s that same aesthetic you’re talking about. And this also brings to mind something else you mentioned during our first weekend of rehearsals: how this dance is about unity but not conformity. A balance of the individual and the community.

So, as both a dancer and a teacher, can you say anything about what that physical experience is like for you—of tapping into that spirit of the legacy? There is something ancestral about the experience when I am doing it. I have a consciousness of those that have come before me and done this piece.

Is it like a conceptual consciousness? Or is it manifested in your body in any way? I know that’s a difficult thing to put into words— I think the consciousness translates physically. I think the physicality affects the consciousness. It goes both ways. I don’t think it’s imposed. I feel like it emerges in the experience and, without getting too metaphysical, you can feel the presence. It’s like traveling through time somehow. …and it can be kind of transcendent in that way.

I think any dance experience can achieve that. It’s like a prayer. It’s like an honoring, an offering.

You can understand why for centuries, across cultures, movement has been used in religious rituals and rites …the “trance state”… Right. And you think of maybe a fertility rite or puberty ritual and you dance this and twenty years later your daughter is doing it, or you see your granddaughter doing it and you remember. You can remember and recall that experience but now you are seeing it from a different sphere of perception.

And do you feel that way when you watch the students you taught dancing it? I do. Yeah, because I’ve been in this environment too, in college learning this dance.